The ideal cross-country ski binding, someone once observed, would be a door hinge attaching the toe of a ski boot to the ski. Considering how simple the objective is, the engineering of cross-country ski bindings became fraught with complexity saw a period of great experimentation (that sounds better, right?).

It’s hard to explain how ridiculously complex nuanced the boot/binding setups have become. During the time I’ve been skiing, there have been no less than twelve different binding systems introduced just for ski touring and racing.

Nerdopolis warning: This is a long post solely about cross-country ski bindings- and I won’t even be talking about changes in the boots and skis. Maybe some other time.

In the beginning was the 75mm three-pin

The original 75mm three-pin binding was developed prior to WWII and represented a design departure from standard cable bindings of the day. It was a competitive advantage in cross-country skiing competitions, and furthered a split between the Nordic and Alpine disciplines in boots and bindings. Subsequent post-war advancements in materials and manufacturing cracked the split wide open.

Crazy decades

The post-WWII economy of North America and Europe also injected middle-class disposable income and leisure time into all sorts of recreational activities. Following Bill Koch’s silver medal in the 1976 Olympics, cross-country skiing grew to its peak popularity in the USA by the early eighties.

Where consumers tread, business will follow. And starting in the late 1970s, the industry tossed boot and binding compatibility out the window in search of performance or popularity. At one point in the early 80s, even Nike tested the waters with a prototype racing shoe.

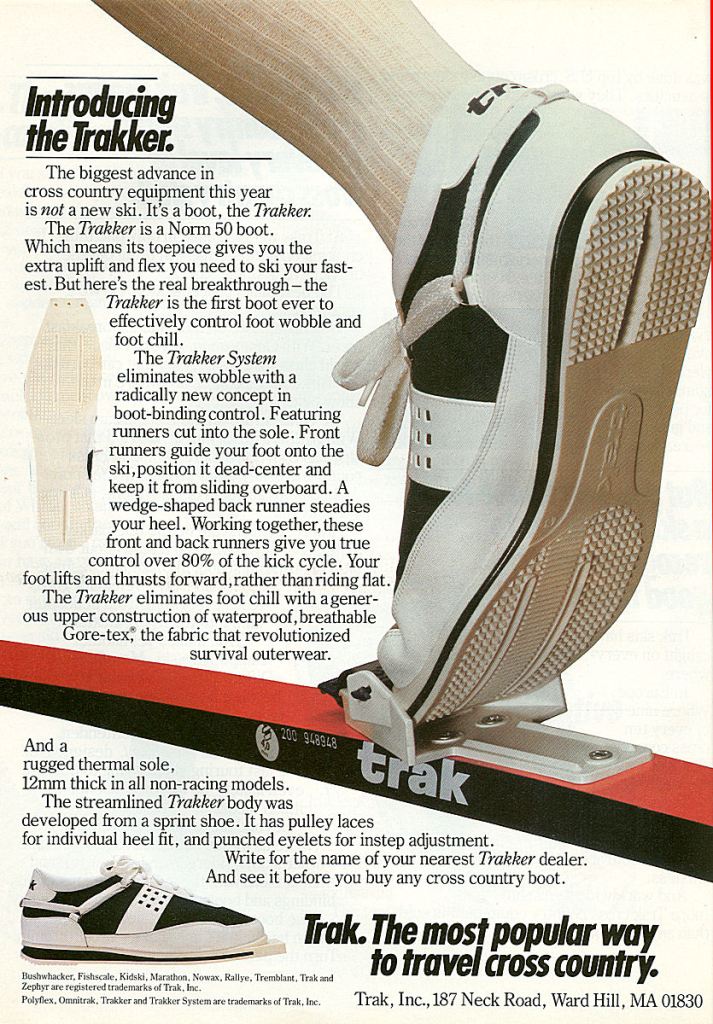

Smelling money in the water, Salomon made a big move into the XC side of skiing, and the deluge was on. In the following list I name distinct binding types introduced for ski touring and racing from the late 1970s to today. In rough chronological order (deep breath): 50mm three pin; Trakker (1970s); Adidas 38mm (1970s); Salomon Nordic System (SNS); Trak (1980s); New Nordic Norm (NNN); Adidas SDS (1980s); Salomon Profil; Salomon Pilot; Nordic Integrated System (NIS v1.0); Salomon Prolink; NIS Xcelerator/MOVE (aka NIS v2.0); IFP Turnamic (2017).

From the mid 1980s till 2015, the situation for retail and rental shops, and skiers who upgraded every few years must have been crazy. Multiple systems existed at the same time and were incompatible by design, sometimes because of a tiny detail. New boots could be incompatible with the bindings on your skis. And if old bindings were out of stock, buying new skis might mean getting a second pair of boots just to fit the bindings available. GRRrrrrr!

That was then: It’s better now. Starting in 2016, Salomon Prolink was designed to be compatible with NNN/NIS, and the newest entry by Fischer and Rossignol, IFP Turnamic, is cross-compatible with the others, meaning boots designed for one will work on the others (as for swapping bindings on a ski, that’s another matter). For a brief review of what’s out there now, See this post about Classic Cross-Country Ski Bindings.

The less good news: Today, several distinct binding systems are still supported, and it’s still possible to get boots that aren’t fully cross-compatible with some bindings. Read a bit about it at the SkiHaus website. This is going to matter when you drag your old cross-country gear out of the closet and decide you want new boots. The Eb’s Adventure website has some history, including a pic of a couple from the 1980s with some radical retro wear and hair.

Even if you know which binding system you bought, the people at a shop might not recognize the name. I recommend bringing your whole setup to a shop for them to check if they can reuse or source your bindings. If you’re going online or mail order and you don’t know your binding system or can’t send them a photo, it might be safer just buying a whole new package.

Backcountry goes its own way

Touring and Backcountry formerly used the same or similar 75mm three pin bindings, but Backcountry began to split off sometime in the 1980s when Telemark skiing became a Thing. First came a heavier-duty three-pin binding for Telemark. Then Rottefella introduced a heavier-duty version of NNN called NNN BC (BC = Backcountry). Salomon followed with a competing product called X-Adventure. Still, through the 90s the good old 75mm three-pin pretty much ruled in Backcountry and Telemark.

If you look at my graphic on the page Types of skis/skiing, General Backcountry skiing equipment becomes more specialized as the terrain gets steeper and more remote. Skis become wider and heavier, leading to stiffer boots, and consequently more rigid bindings.

Binding tech moved on a lot since I lost track of the evolution in XCD. The field now has a wholly different set of complexities nuances. In addition to the old 75mm, NNN BC, and X-Adventure, the NTN Freeride (New Telemark Norm) bindings look like they bear some influence from Alpine Touring tech. Each has tradeoffs in rigidity, weight, price, and field repairability.

This video on Youtube shows a person doing Backcountry skiing at Salt River Pass using equipment that’s designed for Telemark/XCD. Note that the skis are very wide and can use climbing skins like Alpine Touring skis. Yet they also have a waxless pattern in the bottom like touring skis, which Randonnée skis would never have. His boots are plastic with locking buckles like downhill boots, but they flex just a bit at the toe. The bindings fix the boot tightly and a hinge allows Telemark turns, while heel risers make the uphill skiing easier.

Such equipment clearly shows influences from two distinct approaches. On the one hand cross-country; and on the other, a downhill skiing (Alpine and XCD) focus. If you want more info, see these links for Scarpa T4 XCD boot and Voile Switchback X2 binding

Telemark/XCD equipment is overkill for most Backcountry skiing, unless your trips involve terrain that’s pretty steep or in the wild. Those who don’t need an XCD setup but do want to venture into backwoods terrain have other choices, like the aforementioned NNN BC, X-Adventure, or even the classic 75mm three-pin. This second video link compares NNN BC vs. 3-pin bindings. Paired with the appropriate boots and skis, either of them would be an alternative for people who will ski on unmaintained roads and trails or on gentle wilderness terrain.

The following two video links show skiing in conditions that could use Telemark/XCD equipment or rugged Backcountry setups. The skiing in the second video is gnarlier than in the first, and it’s the skier that makes the equipment look good. FWIW, the glimpse I have of the bindings at the end of the video looks like NNN BC.

Yet another Thing: Alpine Touring, or Randonnée

I’ve got little to say about this variant other than that it’s a very specific kind of Backcountry skiing intended for mountainous terrain similar to the Alps. The bindings and boots derive much from Alpine skiing design, but the bindings allow you to release the heel, and boots adjust so you can ski uphill with some mobility.

Given the articles I’ve seen since last fall, I’m guessing some PR firm has been given the commission to promote ‘uphill skiing’ as The New Thing To Do on Snow. Will it find a niche as its own thing, and not just as practice for Alpine Touring? All I know is that it’s a whole other set of boots and bindings, and the sport is too far removed from the kind of skiing I enjoy for me to want to make sense out of it. I’ve had enough trouble keeping up with the touring stuff!

Free heel skiing’s Achilles’ heel: Leverage vs. flexibility

A robust hinge at the toe of the boot to is the logical mechanical engineering solution to allowing a free heel and also transmitting edging force from the boot. It is the design principle for all touring and most Backcountry ski bindings. But there’s a human element as well: the musculoskeletal interaction of foot within the boot.

In cross-country skiing, the foot must be free to flex at the toes and ankle. Yet we also rely on this non-rigid assembly of bone, tendon, and muscle to exert control over twist and rotation of the ski.

The mechanical engineering answer is to design the boot and binding system such that only the defined motions of proper skiing are possible, while augmenting leverage over the ski in every other direction. This kind of thinking is what goes into heavy-duty XCD/Telemark and Alpine Touring equipment. These adaptations are necessary for quick, sure moves on steep terrain, or for control in snowpack that’s inconsistent.

But restraining movement of foot and ankle has downsides. It increases the weight and effort for each stride, hampers the skier’s ability to feel the skis and snow, and creates stresses on other parts of the leg that can result in injury.

This should sound familiar. The same engineering choices took place in Alpine skiing decades ago. Modern downhill bindings and boots buttress stability of the lower leg, but the hardshell boots cause stress to concentrate at the knee. Long ago, when cable bindings didn’t hold the heel down to the ski and ski boots were made of leather, downhill skiing was less tolerant of errors in technique, meaning more injuries overall but the proportion involving the knee was lower.

Of course there’s an engineering answer- augment the knees and legs:

Light touring redux

I find plenty of perceived thrill at the low speeds of light touring, especially when skiing on the narrower trails of some old-timey touring centers. The light and flexible equipment allows me to sense my foot and leg mechanics. The slower speeds give me more time to do something about it, aiding learning. And when I do take a spill, the force of twisting skis dissipates across multiple bends of boots and joints.

The latest breed of light touring and racing bindings are past the peak of elegant simplicity; the elaborations are mainly for racers, who are extra fussy about foot placement on the ski. (How fussy? Read this post on Binding Mayhem at Caldwell Sport, particularly where they describe how to adjust each binding). Regardless, all current bindings are fundamentally a hinge attaching the toe of the boot to the ski. And it’s a relief they’ve left the war of mutual incompatibility behind, so we can focus on getting a pair of boots that fit and forget about binding compatibility for once.

You wouldn’t think a post about something as simple as ski bindings would go on for so long, would you? It’s one of those WTF things about the cross-country ski industry that’s bugged me for a long time. Now that I’ve gotten that off my chest, I’ll just go sit over by the Jøtul and have a glass of Aquavit.

Thanks for reading. Skål!